SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER FOR DISCOUNTS, PROMOTIONS and PRIZES!

The Power of Music in Horror- Part 1

Cinema challenges…it moves, it motivates, it’s humorous, it’s frightful, but most importantly it challenges. The form of which moving images bond to create a film is one that has been studied for decades, particularly in the bounds of visual vs auditory importance. Whilst imagery is a key basis for the resulting composition, film is in fact a mere spectacle without musical arrangements and instrumental structures.

Announcing the history of sound within horror goes back to silent cinema, the time when seemingly noiseless dynamics were not important in regards to the power of music in contemporary cinema. Although the finished product did not emit sound, there were melodic compositions placed over the film to fill in the silent gaps and assist in creating a sinister ambience. As cinema progressed and creatures from the night made their stage presence clear, gothic arrangements utilising the roaring tones from organ instruments became more noticeable, particularly within the Hammer retellings of the reign of villanery seen from the Universal Monsters. Yet, despite the association that classic monster movies have with horror cinema’s sound legacy, it is arguably Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) that fully opened the door for horror to be seen as an audio visual hybrid.

Hitchcock’s deceptive feat conquered the audience’s attention like no other film at the time, switching the entire plot up when it had just started getting juicy, resulting in a scene so memorable, so prolific that it will remain in the horror hall of fame for seemingly years to come. The infamous shower scene saw Janet Leigh at her most vulnerable state whilst a crazed maniac attacks her in a frenzied manner. The scene is brimming with quick cuts and various shots (over 60 of them) and is accompanied by Bernard Herrmann’s orchestral piece titled “The Murder”. Hitchcock originally intended Psycho to have a minimal amount of pieces playing, but his mind was changed once he heard Herrmann’s heightened soundtrack, equipped with screeching violas and violins screeching, almost mimicking the sound of a knife being sharpened.

Pyscho’s “The Murder” has become the theme tune for the entire film, with anyone recalling it immediately humming the slashing jabs made by the plethora of insrutments, somewhat becoming just as famous as the film itself. The idea that a film’s music is just as potent as the feature is an aspect that has continued within horror, particularly with William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973).

As the 1970s kicked in, the horror market was in full swing with the rise of slashers, possession flicks, and exploitation experiments disrupting the flow of family friendly entertainment. And one film that has kept its exceedingly bold reputation throughout history is The Exorcist. Now, to denote such a monumental film’s status on one particular aspect is nonsensical, however, when it comes to this nightmarish religious journey, the score is one of the most vital factors in its ranking.

The theme consists of a strange remix of Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells”, which begins with high pitched tones followed by a falling low rhythm that goes up and down like a terrifying roller coaster of sound. What makes those ringing bells so touching is the use of asymmetrical sound. Just as Oldfield follows an off-sync beat to replicate a turbulent symphony, John Carpenter also employs this technique in what can be defined as horror’s most instantly recognisable themes.

Halloween (1978) has seen a dozen films follow on in the franchise, with all of them having a defining feature whether that be halloween masks, the classic Michael Myers boiler suit, or the various returns of Jamie Lee Curtis. However, Carpenter’s alarmingly haunting score takes the number one spot! The electrical ring that bounces in and out of pitch never meets a resolution, instead a disjointed movement is created, ensuring that a sense of peace is never once felt. Carpenter could have thrown in all the bells and whistles to heighten the score, but instead opted for a simple method that delivers just as much of a startling punch as any grand orchestra.

The 1970s was possibly one of the most experimental times for horror as no particular boundaries were set when it came to creative freedom. Horror filmmakers such as Tobe Hooper, David Lynch, and Wes Craven just went for it, creating an ethos reliant upon what they want to make, not what they “should” make. Aligning with that view are the soundtracks seen within films such as Jaws (1975) and Suspiria (1977), who respectively put horror movie music on the map. Jaws’s award winning score gets right under the skin, making the listener feel as if the flesh-hungry shark is genuinely after you, with the heartbeat-like rhythm intensifying the closer the beast gets to its prey and the high register melody being almost alien to the ear.

In a similar line to the unfamiliarity heard within Jaws soundscape is Goblin’s soundtrack for Dario Argento’s Suspiria. The loose giallo flick is instantly remembered by many thanks to the haunting whispers and witchy curses heard within Goblin’s pieces. The progresive Italian rock band comprises deep baselines and continuous synth notes to not just build up intensity, but to also keep that tension going for long after watching. The film constantly messes with reality, blurring surreal barriers with the film’s actual events, forming an elixir pot for chaos to ensue. Goblin’s continuous hazing of rhythm purposely distracts and contorts the situations even further, aptly aiding in the unearthly route that Suspiria takes.

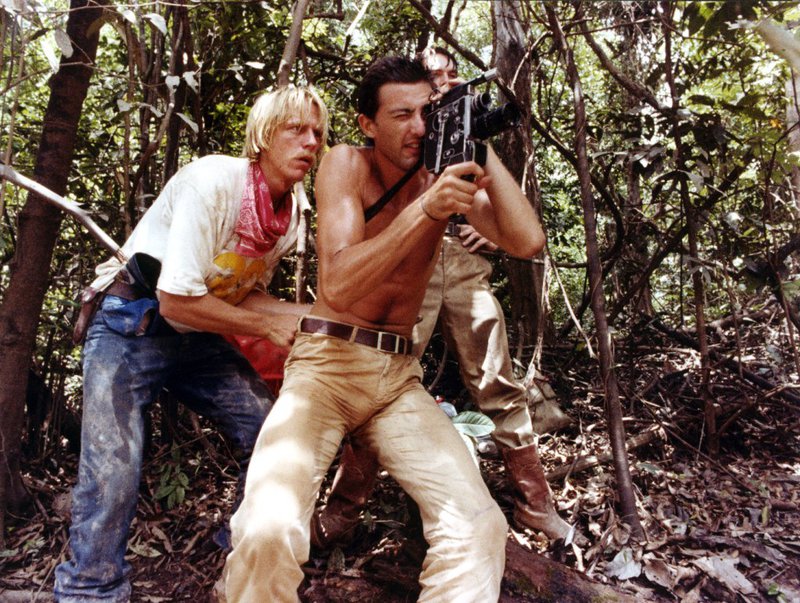

This next film holds the title for being one of the most mainstream controversial horrors to date, with Cannibal Holocaust’s (1980) hidious excursions and unspeakable exploits still accompanying the film to this date. It would be easy to believe that the film’s composer Riz Ortolani would conjure a soundtrack filled with violently smashed together tones to even further disrupt the viewer, instead Ortolani created the most surprisingly dulcet soundtrack to have ever come from a disturbing horror. The melodies are gentle, almost akin to a lullaby, lulling the viewer into a false sense of security and distorting the overall narrative to be somewhat surreal.

Cannibal Holocaust’s airy juxtaposition is not the only horror to feature an overtly drastic difference between visual and audio, with American Werewolf in London (1981) being jampacked with carefully selected tunes to set the scene. John Landis’s upbeat soundtrack had no qualms in apperaning too on-the-nose, with songs such as “Blue Moon” (Bobby Vinton) and “Bad Moon Rising” (Creedence Clearwater Revival) playing over the werewolf transformation scenes, nicely pairing the cheery songs with the mabare body horror escapades being graphically presented on screen.

![An American Werewolf in London' and Its Iconic Transformation [It Came From the '80s] - Bloody Disgusting](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/american-werewolf-london-e1585840708232.jpg)

As time progressed so did movie music. The 1980s still dominates pop culture to this day; the soundtrack for the decade bounced between melodic ballads and free-spirited pop to punk inspired shredding and metal mania tracks. As film largely takes shape based on the environment surrounding it, it’s safe to say that 1980s horror was brimming with some of the most creative scoring ever seen, with The Lost Boys (1987) being true to this theory in every way possible.

The Californian vampiric beachside setting of Santa Carla sets up the perfect playground for composer Thomas Newman and director Joel Schumacher to take the viewer through a creepy carnival of 80s hit songs paired against dark and stirring arrangements. The film has become synonymous with Echo & the Bunneymen’s cover of The Doors “People are Strange”, INXS and Jimmy Barnes chart topping “Good Times”, and the film’s main theme original song “Cry Little Sister” that goes above and beyond in emulating the The Lost Boys moody, leather clad aura. Not to forget to mention the absolute iconic cover of “I Still Believe” (The Call) performed by Tim Cappello, or the shirtless saxophone playing bodybuilder as many may know him.

Another section of movies that saw an influx of interest thanks to music is comedy horror, particularly those who unlike Cannibal Holocaust stayed on the lighter side. Ghostbusters (1984) may not appear on every ‘horror movie list’ as technically the supernatural ventures won’t necessarily send shivers down your spine, yet, there’s just something so classic and synonymous with the Ghostbusters theme song and halloween culture that it’s impossible to not alert the film’s significance.

Appropriately named “Ghostbusters” is Ray Parker Jr’s. smash hit that was even nominated for an Academy Award (57th) for Best Original Song, where the catchy chorus will have even the most stern audiences singing along. On a similar note is Beetlejuice’s (1988) use of Henry Belafonte’s “Day-O” in which an elegant dinner party is ruined by the guests uncontrollably singing Belafonte’s hit in a bizarre and ultimately hilarious fashion.

Over time the use of music in cinema has metamorphosed to suit the times, whether that be the inclusion of classic songs from the thirty years prior to highlight a character’s personality, or even the addition of newer musical genres to spice up the screen. However, one thing has not changed at all, and that is the integral importance and power that music holds over cinema.

Looking for more top horror lists and reviews? Check out our blog here..

Share this story